The Watershed Council has coordinated and sponsored the Volunteer Lake Monitoring Program since 1986. Presently, volunteers monitor 29 lakes spread throughout Antrim, Charlevoix, Cheboygan, Emmet, and Montmorency Counties (map below). The objectives of the program are to collect baseline data, characterize lake ecosystems, identify specific water quality problems, determine water quality trends, and, most importantly, inform and educate the public regarding water quality issues and aquatic ecology. Monitoring water quality does not ensure clean water, but rather provides valuable information to help protect and improve water quality in the lakes of northern Lower Peninsula of Michigan.

What does a Volunteer Lake Monitor do?

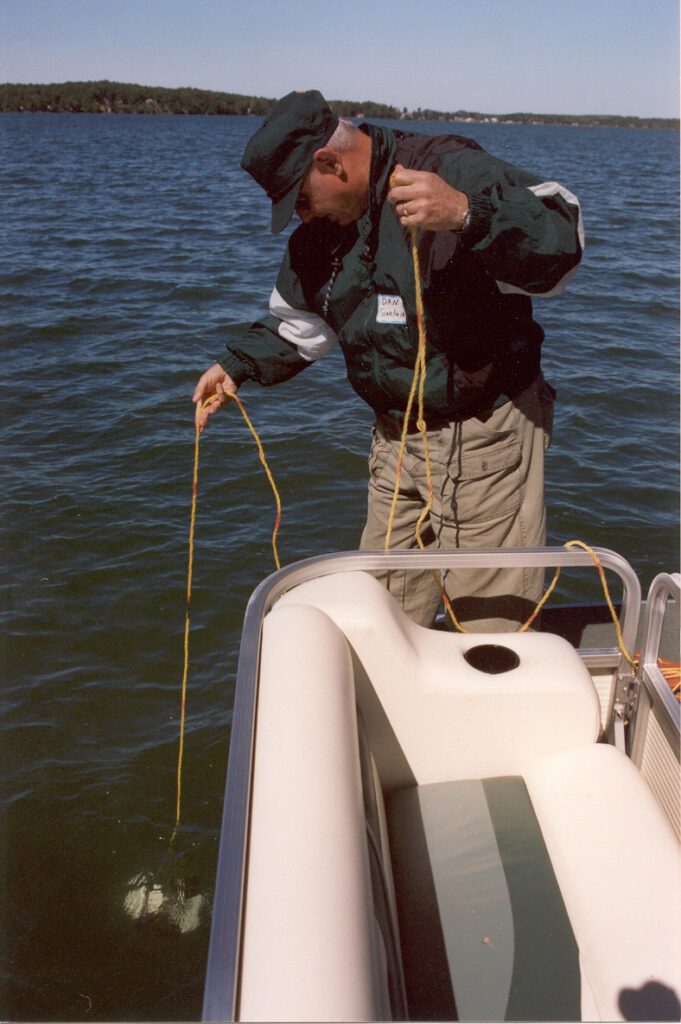

Volunteer lake monitors are often the first people to get their boats in the water in the spring. Starting in May or early June, they start their weekly visits to the deepest part of the lake to perform water quality monitoring activities. After anchoring the boat, the monitor begins by measuring water clarity with a Secchi disc.

The Secchi disc method was originally developed by Italian scientist, Pietro Angelo Secchi, in 1865 and, due to its simplicity and reliability, remains one of the most widely used water quality monitoring instruments today. It is a weighted disc, eight inches in diameter, which is painted black and white in alternating quarters. The monitor slowly lowers the Secchi disc over the shaded side of the boat and notes the depth where it disappears. The disc is lowered an additional two feet and then slowly raised until coming back into view. After noting the depth of reappearance, the average of the two depths is calculated and recorded. The deeper the Secchi disc depth, the clearer the water and generally the better the water quality.

Every other week, the monitor collects a water sample that is used to measure chlorophyll-a concentrations. Chlorophyll-a is a pigment found in all green plants, including algae. Measuring the amount of chlorophyll-a in a water sample provides a fairly accurate estimate of the amount of algae in the water. After determining the Secchi disc depth, the monitor collects the water sample in the same location. An ‘integrated sampling device’, which is a weighted container with a small hole on the top for water entry is lowered down through the water column to twice the Secchi disc depth. Research has determined that sunlight penetration, and therefore plant growth, is limited to approximately two times the Secchi depth. The water sample has to be representative of the entire water column, so the volunteer has to lower and raise the water sampling device at such a rate that twice the Secchi disc depth is reached and so that the container is not overflowing upon reaching the surface. Although more difficult than measuring Secchi depth, with practice our volunteers have consistently and quickly mastered this water sample collection method.

Once the water sample has been collected, the volunteer monitor uses a syringe filtering device that forces a specific volume of water through a filter paper. The filter paper is carefully placed into a test tube, wrapped in tinfoil to prevent exposure to sunlight and stored in the freezer. At the end of the sampling season, the accumulated test tubes with filters of all the lake volunteer monitors are delivered to a lab for analysis. A low level of chlorophyll-a indicates relatively low algae abundance and good to excellent water quality, while a high level of chlorophyll-a indicates dense algae growth and generally poor water quality.

Lake Characterization and Trophic Status

All lakes undergo a natural “aging” process called eutrophication. Lakes formed from glaciers are often very deep, with cold water, low levels of nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen), and low biological productivity (relatively little aquatic life). As a lake “ages”, nutrient accumulation in the lake water and bottom sediments leads to greater biological productivity. Greater biological productivity leads to increased deposition of organic matter, which, combined with sediments that wash in during rain storms or snowmelt, cause the lake to become shallower and water temperatures to rise. In a natural setting this process occurs very slowly with little or no apparent change over the course of a human lifetime.

Human activities in a watershed often greatly accelerate the natural aging process of lakes by contributing additional nutrients and sediment. The acceleration of the process is called ‘cultural eutrophication’. When excessive nutrients are added to a lake, aquatic plants and algae thrive, resulting in excessive growth and large blooms. Excessive plant growth and large algae blooms can make swimming undesirable, make boating difficult and lead to the formation of ‘dead zones’. Dead zones are areas in a water body devoid of aquatic life due to dissolved oxygen depletion. Although aquatic plants and algae contribute oxygen to the ecosystem during day-time photosynthetic activities, they consume oxygen during the night while respiring, which (with excessive plant growth) can result in oxygen depletion. Increased sediment contributions from erosion, construction activities, and other human activity also accelerate the aging process.

Putting the Data to Work

Data collected by volunteers in the Volunteer Lake Monitoring program are used by Watershed Council staff to determine the current level of productivity or the “trophic status” of a lake using Carlson’s Trophic Status Index (TSI). This index utilizes Secchi disk depth recordings and chlorophyll-a measurements collected by volunteer monitors to calculate a lake score that ranges from 0-100. Lakes that score at the low end of the scale (TSI values ranging from 0-38), are considered to be oligotrophic with excellent water quality. A TSI score of 39-49 indicates a mesotrophic lake with good water quality and a TSI value of 50 or greater is considered to be a eutrophic lake with poor water quality. However, keep in mind that eutrophic lakes occur naturally during the aging process and do not necessarily reflect poor water quality.

Many beautiful high-quality lakes are being monitored by volunteers throughout the northern Lower Peninsula as a result of the Volunteer Lake Monitoring Program. Nevertheless, there is always a need for more volunteers. Call (231) 347-1181. Volunteering to be a monitor requires attending a half-day training session and then performing 1-4 hours of monitoring duties on a weekly basis from early June to late August (though some volunteers opt to start in May and continue until September or even October!). If you are interested in volunteering time to help monitor lake water quality, please contact the Watershed Council office at (231) 347-1181.

For Volunteer Lake Monitoring Data, Click Below