State Permitting

Many pipeline projects take place on or near a land/water interface including, a lake, river, Great Lake, pond, dam, wetland, floodplain, drain, ditch, swamp, shoreline, stream, creek, or marshland. These projects are regulated by the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) Water Resources Division. The main laws for pipeline projects that impact water resources are:

- Part 301 Inland Lakes and Streams, of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (Act 451 of 1995), requires permits to dredge, fill, or construct, or place structures below the ordinary high water mark and connect any waterway to an inland lake or stream.

- Part 303, Wetland Protection, of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (Act 451 of 1995), requires a permit to fill, dredge or remove soil from a wetland, construct, operate, or maintain a use in a wetland, or drain surface water from a wetland.

- Part 325 Great Lakes Submerged Lands, of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (Act 451 of 1995), regulates construction activities along the Great Lakes shoreline and the over 38,000 square miles of Great Lakes bottomlands, including coastal marshes.

While each law has its own language and specific provisions, in general, all of the statutes are designed so that permitted pipeline projects avoid and minimize potential adverse impacts to Michigan’s water resources and mitigate for those impacts that do occur.

Each law requires that pipeline projects consider the following:

- Alternatives – prohibits issuance of a permit for projects where feasible, less environmentally damaging alternatives are available.

- Adverse Impacts – prohibits issuance of a permit for projects which would cause or contribute to significant adverse impacts to the aquatic environment.

- Water Quality – prohibits issuance of a permit for projects which would violate any applicable State water quality standard.

- Mitigation – requires project applicants to eliminate avoidable impacts and to minimize and compensate for unavoidable impacts.

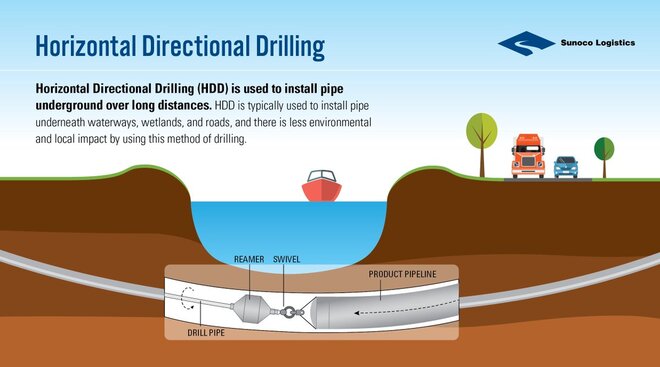

Under Part 301, Inland Lakes and Streams, there is a rule (R 281.832) which exempts horizontal directional drilling for lake and stream crossings if the top of the pipeline is at least 10 feet below the bottom of the lake or stream and the entry and exits points are far enough away to not cause bank disturbances and are outside any natural river designation setback requirements. This exemption is only allowed up to 10,000 feet.

Public Notice for State Permit Applications

The first step of participating in the water resources permit process for pipeline projects in Michigan is to obtain information regarding permit applications and public processes with opportunity for public comment. Most public notices, unfortunately, go virtually unnoticed by the general public until it is too late. However, there are ways for you to be aware of permit applications.

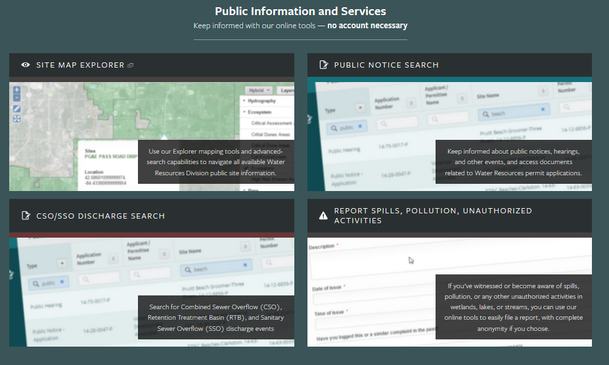

The Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) has an online permit tracking system called MiWaters. From the home page, you can access the Water Resource Division’s permitting programs, including public notice and public hearing listings, search active or past permit records, access permit applications, and report complaints (e.g., placing fill in wetlands), spills, or pollution events (e.g., petroleum products in water). It allows you to search for permit applications using criteria such as year, county, township, waterbody, file number, and applicant name. The MiWaters home page can be accessed by following this link: https://miwaters.egle.state.mi.us/miwaters/external/home.

In addition to MiWaters, EGLE has an interactive environmental calendar designed to provide timely information on decisions before the Office of the Director, proposed settlements of contested cases, administrative rules promulgation, public hearings, meetings and comment deadlines, and environmental conferences, workshops, and training programs. You can subscribe to receive calendar updates via email at https://eventactions.com/eventactions/egle-events#/subscribe.

Often, pipeline permit applications will be processed as a general or minor permit. General and minor permits are not subject to public notice, and subsequently, not able to be commented on. There is a general permit for “Pipeline Safety Program Designated Time Sensitive Inspections and Repairs,” which is for the maintenance and repair of oil and gas pipelines that cross inland lakes, streams, and wetlands, in particular, as required by the provisions of the Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002, under certain conditions. There is also a minor project category for activities required for the construction, maintenance, repair, and removal of utility lines and associated facilities in wetlands, inland lakes, and streams. EGLE may choose to issue a public notice and call for comments even if an activity is otherwise covered by a general or minor permit. This is done for permit applications of great interest to the public, such as Enbridge Line 5 permit applications.

The opportunity for public comment is provided for if EGLE issues a formal public notice. A public notice is issued for individual applications. Once the public notice is issued, the public has 20 days to submit written comments on the proposed pipeline project.

Contested Case Hearings

All citizens are provided the opportunity to file an administrative appeal to contest any action or inaction of a State agency. The contested case hearing process is commonly used by applicants to contest permit denials, but can also be used to contest permit issuances or other regulatory activities (often called “third party contested cases”). Contested cases are presided over by an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) from the Michigan Office of Administrative Hearings and Rules (MOAHR). The contested case hearing process is governed by the Administrative Procedures Act (MCL 24.201 et seq.) and administrative rules (R 324.1 et seq.).

There are two major drawbacks to contested case hearings: 1) it does not provide injunctive relief, and 2) they take a long time. As a result, third party contested cases can be filed, but the contested activities done in compliance with an issued permit can still continue until the process is complete. For this reason, lawsuits requesting injunctive relief are usually filed along with the contested case hearing request.

Federal Permitting

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) has authority to issue permits for activities regulated under Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act and on select waters under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act. Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 provides the USACE with jurisdiction over work waterward of the Ordinary High Water Mark (OHWM) of navigable waters. Additionally, the USACE jurisdiction may extend to the landward side of the OHWM of navigable waterbodies if activities in those areas could affect the course, location, or condition of the waterbody so as to impact its navigable capacity. A tunnel, pipeline, electric line, or other structures or work over or under a navigable water is considered to have an impact on the navigable capacity of the waterbody.

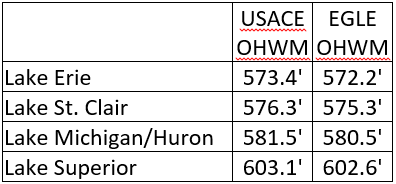

The OHWM is established by the fluctuations of water and is indicated by physical characteristics such as a clear and natural line impressed on the bank, shelving, changes in the character of the soil, the destruction of terrestrial vegetation, or the presence of litter or debris. For regulatory purposes, the OHWM is the elevation along the shoreline where a permit is required. The elevation reference system used to define Great Lakes water levels is the 1985 International Great Lakes Datum. The OHWM for the Great Lakes are provided and note that the USACE and EGLE have slightly differently OHWM elevations.

In Michigan, under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, the USACE regulates discharging dredged and/or fill material into navigable waters used for international and interstate commerce, such as the Great Lakes and connecting channels, and in any wetlands adjacent to those waters. Often times, the State and Federal permits are submitted together under a “Joint Permit Application.”

Just like the State, the USACE Detroit District has an online permit tracking system for public notices. You can request to be added to the Public Notice Electronic Mailing List. This allows you to receive Public Notices by email for select county(s) that you have requested. You can access the USACE Public Notices for Michigan, along with the form to the Electronic Mailing List, at https://www.lre.usace.army.mil/Missions/Regulatory-Program-and-Permits/Public-Notices/.

The USACE also has the authority to issue general permits which may not be public noticed. The USACE has a Nationwide Permit (NWP) 12, which authorizes activities required for the construction, maintenance, repair, and removal of utility lines and associated facilities in waters of the United States, provided the activity does not result in the loss of greater than 1/2-acre of waters of the United States for each single and complete project, subject to certain conditions.

There is also a Regional Permit for submerged utility line crossings across federal navigable waterways. Regional Permits authorize activities of a minor nature in approximately five to 15 work days, provided the application is administratively complete, and reduces costs, delays, and paperwork for the applicant and USACE.

Just as the State, the USACE may choose to issue a public notice and call for comments even if an activity is otherwise covered by the NWP 12 or Regional Permit K for permit applications that may be controversial or of significant public interest.

The Citizen’s Role in Water Resources Permitting

Your role in evaluating permit applications is very important to the wetlands and water resources protection process. Not only do citizens provide valuable information, but they also serve as a reminder to agency staff that the purpose of the regulations is to protect the public’s interest in Michigan’s water resources. In this sense, public participation helps to ensure that regulatory staff are accountable to the public interest. The process described below presents a simple procedure to help you analyze public notices and describes how to effectively participate in State and Federal water resource permitting.

Assuming you have taken the steps to receive a public notice, there are important pieces of information contained in the public notice of which you need to be aware. These pieces of information include:

1) The date the public notice was issued and the date comments are due by (EGLE will receive public comment for 20 calendar days from the issue date).

2) The application file or submission number (this number should be included in any correspondence).

3) The project location (this is helpful when trying to investigate the site).

4) Adjacent landowners (these individuals are often very helpful in providing information about the site).

5) The type and extent of the activity (this is critical when assessing project impacts).

6) The purpose of the proposed activity (this is critical when determining if there are available alternatives).

To be most effective, any individual or group commenting on an application should have first-hand knowledge of the water resources of each site in order to determine the potential project impacts. Fish and wildlife values, shoreline stabilization values, hydrologic values, endangered or threatened plants and animals, nutrient and sediment retention capabilities, recreational uses, and any other impacts should be identified.

The effectiveness of your comments will depend upon how relevant they are to the regulatory standards that the agency staff must apply. In reviewing both the USACE and EGLE public notices, there are three main questions you should always consider. These questions effectively summarize the regulatory standards.

1) Do feasible and prudent (or “practicable” in USACE permits) alternatives exist? If the project is not dependent upon being placed in a wetland or water resource, then less damaging alternatives are presumed to exist. Although by law the applicant has the burden of proving that no alternatives exist, often the alternatives analysis provided by the applicant is very superficial. Common alternatives that minimize impacts include the use of upland building sites, alternate methods of construction to minimize fill, or using different techniques such as horizontal directional drilling. Remember, alternatives can also include practicable alternate locations not presently under the applicant’s control but reasonably available. Local knowledge regarding alternatives can be very important. Because local citizens are familiar with the area in question, they may know about alternatives (such as available land or other access sites) that are not apparent to the regulatory staff.

After answering the questions above, you must determine whether or not to take action. If the project has no alternatives, is in the public interest, and will have an acceptable disruption on the aquatic resources, then there is no need for further involvement. However, this is seldom the case. In practically all cases, you can provide comment valuable to the permitting process. The most effective ways to provide comment are through letters and at public hearings.

It is important to understand that public hearings have their shortcomings. These shortcomings arise from the disparity between agency staff obligations and citizen expectations. The technical purpose of a public hearing is for the agencies to gather public comment on only those issues that are pertinent to the specific statute being implemented. The public often requests a public hearing because they desire a public forum to discuss all aspects of a proposed project. They are frustrated when the USACE or EGLE hearings officer does not answer their question or consider relevant those comments that are not germane to the statute. An alternative to this is to call for, and in many cases coordinate, a public meeting. This provides the opportunity for you to discuss all issues related to the project.