The waters of the Great Lakes are, for the most part, a nonrenewable resource. They are composed of numerous aquifers (groundwater) that have filled with water over the centuries, waters that flow in the tributaries of the Great Lakes, and waters that fill the lakes themselves. Although the total volume in the lakes is vast, on average less than 1 percent of the waters of the Great Lakes is renewed annually by precipitation, surface water runoff, and inflow from groundwater sources.

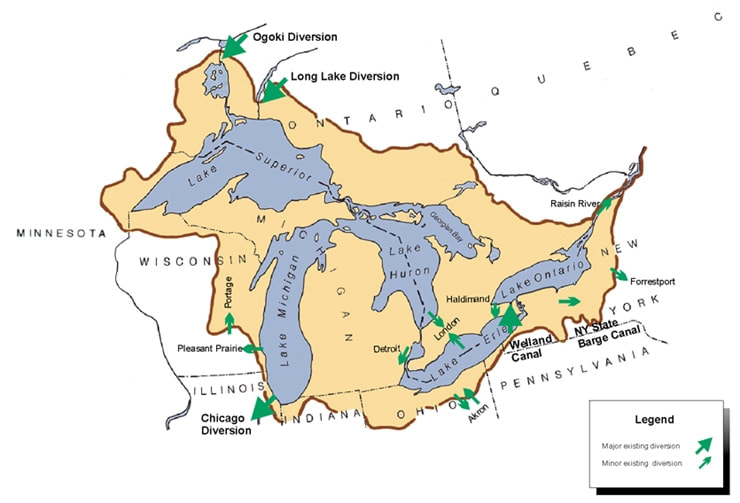

A diversion is any transfer of water across watershed boundaries through a man-made pipeline or canal. Diversions may transfer water in or out of the Great Lakes basin, or between the watersheds of different lakes or rivers within the basin. While the impacts of existing diversions on lake levels are minor, they alter the natural flow of the Great Lakes and water returned from diversions may be of a different quality than when it was withdrawn.

Current Great Lakes Diversions

Credit: International Joint Commission

The Chicago diversion from Lake Michigan into the Mississippi River system is the only major diversion out of the Great Lakes Basin.

The Long Lac and Ogoki diversions into Lake Superior from the Albany River system in northern Ontario are the only major diversions into the Basin. The Long Lac and Ogoki diversions represent 6 percent of the supply to Lake Superior. (At present, more water is diverted into the Great Lakes Basin through the Long Lac and Ogoki diversions than is diverted out of the Basin at Chicago and by several small diversions in the United States.)

The Welland and Erie Canals divert water between sub-basins of the Great Lakes and are considered intrabasin diversions. Aside from these major diversions, there are also a few small diversions:

- Forestport, New York diverts waters of the Black River into the Erie Canal and the Hudson River watershed

- Portage Canal diverts Wisconsin River waters (Mississippi Basin) into the Great Lakes Basin.

- London, Ontario, and Detroit take water from Lake Huron for municipal purposes. London and Detroit discharge their effluent to Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River, respectively

- The Raisin River Conservation Authority in New York takes water from the international section of the St. Lawrence River to maintain summer flows in the Raisin River

- The communities of Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin, and Akron, Ohio, which lie outside the Great Lakes Basin take water from the Great Lakes on the condition that they return an equivalent volume of water over time to the Basin

- Haldimand, Ontario takes water from Lake Ontario

Diversions of water from the Great Lakes are currently negligible. However, an increasing number of droughts and climate change from global warming may result in more arid conditions in southern, central, and western US. Moreover, the US population is expected to swell by 50 percent – an additional 150 million people – in the next few decades, thus exacerbating water needs. As fresh water supplies are dwindling in the American West and South, and US states surrounding the Great Lakes experienced increasing pressure to divert water to dry parts of the country.

Water diversions from the Great Lakes on a large scale could have serious consequences. Proposals to divert water from the Great Lakes hydrologic system have proven very controversial.

Requests for Diversions and Exports of Great Lakes Water

- 1981 Powder River Coal Company is denied a diversion of Great Lakes water to Wyoming to feed a pipeline that would carry coal slurry to the Midwest.

- 1982 The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers studies and denies a diversion of Great Lakes water to recharge the Ogallala Aquifer that underlies 8 states from South Dakota to Texas.

- 1990 Pleasant Prairie, WI, gains approval for a temporary 3.2 mgd diversion from Lake Michigan for public supply. The village must return treated wastewater to the lake by 2010.

- 1992 Lowell, IN, is denied a 2 mgd diversion for public supply (vetoed by governor of Michigan).

- 1998 Akron, OH, gains approval for a diversion from Lake Michigan of up to 4.8 mgd (an average 0.32 mgd is diverted) for public supply.

- 1998 The Nova Group gains a permit from the Ontario Ministry of the Environment to export approximately 160 million gallons per year (an average 0.4 mgd) of Lake Superior water to Asia in bulk containers. The permit is revoked due to objections of Great Lakes governors and citizens.

- 2006 New Berlin, WI, applies for 1.83 mgd (and up to 2.48 mgd by 2050) of Lake Michigan water for parts of the community outside the Great Lakes basin. As of early 2008, New Berlin is in discussions with Milwaukee about a potential sale of Great Lakes water, and has not resubmitted its application to the DNR.

As these lakes are a shared international resource, many governments and organizations are concerned with managing and protecting the integrity of the Great Lakes waters and ecosystem. For these groups, the bulk export of Great Lakes basin water became an increasing concern in a water-scarce world. In order to protect the Great Lakes from commercial interests hooking up pipelines and sending tankers to deplete the Lakes, the Great Lakes Compact was developed.

Great Lakes Compact

The Great Lakes – St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact (the Compact) bans large-scale diversions from the Great Lakes and establishes a consensus-based process for managing the region’s waters. It also is a catalyst for state and regional water conservation measures. Additionally, it sets uniform standards for monitoring new water withdrawal proposals within the basin.

This formal, interstate compact has the force of a federal law, with standing in federal court. It was signed by all eight Great Lakes state Governors in December 2005. It then began a journey that included being passed by each of the eight state legislatures, ratified by the United States Congress, and finally signed into law by the President on October 3, 2008.

The Compact is an agreement among the eight Great Lakes states to prevent diversions and withdrawals that would harm the ecosystem created by the waters of the Great Lakes. It is rooted in history and a long tradition of managing the lakes cooperatively. Importantly, the Compact treats groundwater and surface water as one system subject to the same standard, and also includes the following statements about the Waters of the Great Lakes:

- They are valuable public resources held in trust by the States;

- They are interconnected and part of a single hydrologic system;

- They can concurrently serve multiple uses; and

- Future diversions and consumptive uses have the potential to significantly impact the environment, economy, and welfare of the region.

The Compact, rooted in conservation, also includes some exceptions for vital economic and agricultural activities carried out across the basin. This allows domestic commerce and international trade activities to go on. None of the exceptions invalidate the primary motivation of the Compact to conserve the waters of the Great Lakes. The Product exception, for example, allows water to leave the region if it is used to make something. This means that water used in the process of manufacturing goods, or to make items such as baby food or cherry jelly, and shipped out of the basin is not considered a diversion. However, the Great Lakes states may still regulate withdrawals of water used to make a product so that the ecosystem is protected.

Michigan Water Use Laws

New laws became effective February 28, 2006 amending Part 327 and 328 of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act and the Safe Drinking Water Act. The amendments address reporting registering, environmental protection standards, and permitting requirements for large quantity water withdrawals from ground and surface water.

On July 9, 2008 Governor Jennifer Granholm signed legislation that passed the Great Lakes Compact in the state of Michigan. This legislation also included new water withdrawal laws that are groundbreaking, taking a positive step to protect our water resources for generations to come. Key points in the law include:

- Protecting against “adverse impacts”

The new law reserves at least 75% and in some cases up to 95% of the summer low-flow of rivers and streams to protect aquatic health. As cumulative withdrawals get closer to this line, more public input, state oversight and review of possible water conservation measures are required. - State Oversight

The threshold for state permits to withdraw water from the Great Lakes was lowered from 5 million to 2 million gallons a day. Additionally, the threshold from inland sources is lowered from 2 million gallons a day to 1 million gallons a day in sensitive areas. The thresholds for water bottling plants are lowered to new plants or expansions over 200,000 gallons a day. - Public Participation

The law involves the public through new “water use assessment and education committees” when withdrawals start to have minor impacts in stream flows. Groups working on local water quality issues are notified and given the opportunity to be involved in reviewing local water use and efforts to use it efficiently. Public notice and participation is required for any facility that requires permitting. - Conservation

Since 2006, water use sectors have been developing environmentally sound and economically feasible water conservation practices. The new law requires water users to self-certify that they reviewed these practices, and are implementing cost-effective practices in some instances.

Additional Resources

(Data above modified from information compiled by International Joint Commission)